Against all odds — and with a little help — homeless students find a brighter future

Published on: Miami Herald

By: Kyra Gurney

Click Here to View the Original Article

One month into his senior year of high school, Terrence Nickerson found himself homeless and alone.

Terrence Nickerson attends Florida International University. In high school, he was homeless during his senior year.

CHARLES TRAINOR JR ctrainor@miamiherald.com

He had been kicked out of his step-father’s house after an argument and had no money, no nearby family and nowhere to go. After crashing with friends for a month, Nickerson wound up at a homeless shelter in downtown Miami, in a large dormitory where 100 men slept in wall-to-wall bunk beds. For the first week he was there, Nickerson walked from the Chapman Partnership shelter on North Miami Avenue to Miami Jackson Senior High School in Allapattah — over an hour each way.

It would have been enough to demoralize anyone, especially a teenager with no family to rely on. But Nickerson was able to tap into a network of support at the shelter, at his high school and through Project UP-START, an office in the Miami-Dade school district that supports homeless students. He got transportation to school so he could keep going to Miami Jackson and help to apply for college, earning a scholarship and taking advantage of state tuition waivers for homeless and foster youth to attend Florida International University, where he is now a freshman.

“Being at the shelter, it changed my whole mindset,” said Nickerson, who is now 19. “I felt pretty supported mainly.”

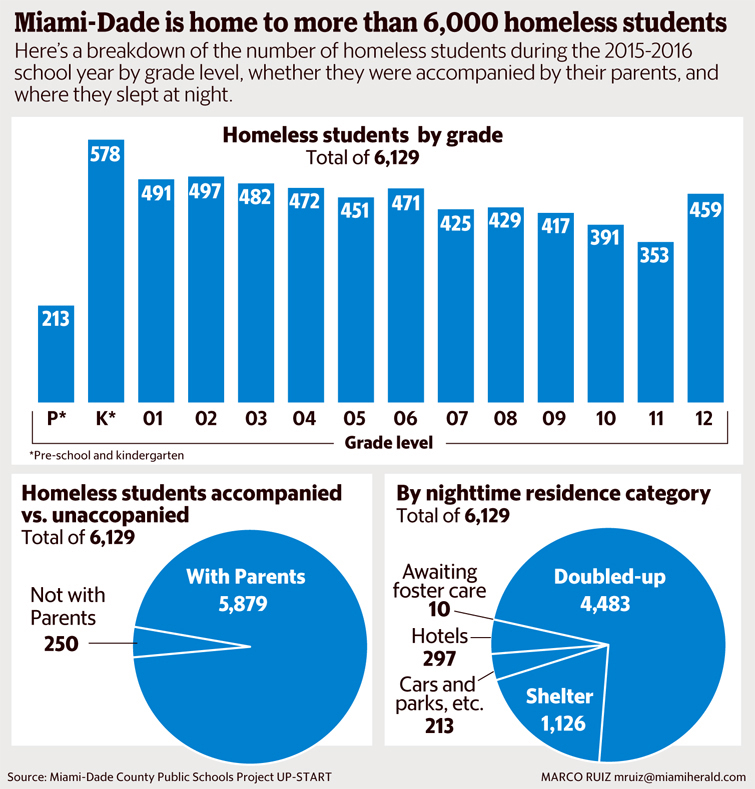

Nickerson now lives in the FIU dorms, but last school year he was one of more than 6,000 students in Miami-Dade without a stable place to live. That includes students who sleep in homeless shelters, on the street, in a car, in a hotel room or squeezed into someone else’s home — known as “doubling up.” In the face of seemingly insurmountable obstacles, many homeless students like Nickerson are succeeding in school and finding a brighter future, thanks in part to the support of programs like Project UP-START in the school district and similar initiatives at FIU and Miami Dade College, which help homeless students take care of basic needs so they can focus on doing well in school.

“We provide a sense of support for the kids and families going through this to explain to them that they’re not alone,” said Debra Albo-Steiger, Project UP-START’s program manager. “One of the hardest parts about this situation is that you feel so alone and you don’t want to tell anyone.”

Project UP-START was created in 1992 and has grown considerably in recent years, helping students enroll in school, get signed up for free lunch, and find transportation so they can keep going to the same school, which can be a challenge for families moving from one end of the county to the other in search of shelter. Project UP-START also has a store at Lindsey Hopkins Technical College where homeless families can get clothing, shoes, toiletries and food — all of it free.

It’s a program that is near and dear to the heart of Miami-Dade Schools Superintendent Alberto Carvalho, in part because he was homeless as a young man.

“It’s very personal for me,” said Carvalho. “I remember the feeling of the cold concrete as your mattress and the stars as your blanket as well, and I know what it’s like to feel that constant rumbling in my stomach. There is no reason as to why we should accept any child in Miami or for that matter in America to feel that way.”

Although the official figure puts the number of homeless students at 6,129 for the 2015-16 school year, the most recent period for which the figure is available, Albo-Steiger believes the actual number is closer to 10,000, because students living doubled-up with friends or family are often too embarrassed to tell school staff. A crucial part of Project UP-START’s work is training school staff to identify students whose families lack permanent shelter so they can take advantage of support services.

“Rental prices in Miami-Dade County have skyrocketed, so we have a lot of families who are working, especially with single mothers, but who can’t get the money for the deposit and first and last month’s rent,” Albo-Steiger said.

The most vulnerable students, however, are often the ones like Nickerson who find themselves homeless without their parents. These are students who may have gotten kicked out of their homes because of a fight with family members or who may be running from abuse. Some of these young people end up at Miami Bridge Youth & Family Services, an emergency shelter with two locations in Miami-Dade that provides temporary refuge for children who have been trafficked, who are between foster care placements, or who need a temporary reprieve from a volatile family situation, in addition to homeless youth.

Miami Bridge has schools on site at both of its locations so students don’t lose any class time while waiting to return to their families or find more permanent housing.

Kris Pullock had to leave his home at the age of 17 and ended up at Miami Bridge in August, where he stayed until turning 18 in early November. Before going to the shelter, Kris said he skipped class frequently, but having a school just steps away from where he was living helped him stay on track.

Kris Pullock, a homeless student at Miami Bridge Youth & Family Services, poses on the patio during a break on Sept. 14, 2016. PEDRO PORTAL pportal@miamiherald.com

“I was getting in trouble doing stuff I was not supposed to do,” Pullock said in September. “Here I’m more focused, there are less distractions.”

The Miami Bridge school is staffed by teachers from the school district, who provide each student with assignments based on his or her grade level. “The teacher is more available to help and I take it more serious,” said Pullock, whose plan now that he is 18 is to go to Job Corps, an adult learning center where he can get his GED and study a trade. “I’m on the right path,” he said.

Dorcas Wilcox, the CEO of Miami Bridge, said she sees many students who might not have been successful in traditional schools flourish with fewer distractions at the on-site school.

“They may kick and scream when they first get here, but then they’re excited to come and show me their report cards,” she said.

Many of the students at Miami Bridge have experienced trauma in their lives and Wilcox said she is impressed by the resilience of the teens, who often keep in touch long after they’ve left the shelter.

“The stories that they have, and to watch them overcome, I just feel like a proud mom,” Wilcox said. “We just show them love and attention. You’d be surprised by how far that goes.”